Adaptive Challenges Require SysQ

It seems like we are now facing a range of challenges more expansive than we faced even a few short years ago—it feels daunting. And the complexity of these issues is significantly more tangled and dynamic. Worse, the pace of complexity increasing is accelerating. In short, the persistent issues we face—what are defined as adaptive challenges—are complexifying. The only way we can get out in front of these challenges is to rapidly build our collective systemic intelligence (SysQ).

WORKFORCE ISSUES

Some challenges we see rapidly complexifying can be defined as organizational in scope, more workforce/workplace issues. For example:

Diversity/Equity/Inclusion

Demographics

On-site vs. Virtual Work

Organizations are struggling to address the now impossible to hide—and difficult to overlook—issues of inequity in the workforce and workplace. From the private to public sector, organizations are implementing Diversity/Equity/Inclusion (DEI) initiatives. The intergenerational workforce of today may have the most diverse range of demographics in history—Boomers raised in the Cold War are on teams with young Gen Y, who have grown up on smart phones and haven’t a clue what dial up means. And the recent pandemic has accelerated the shift from 100% onsite to nearly 100% virtual work for many fields and industries. Experts predict the consequences of the pandemic will change how we work for decades.

ECONOMIC DISRUPTIONS

Other challenges are more related to the interconnected and digital global economy, like:

Cybersecurity

Disruptive innovations

Cryptocurrency

The epidemic of malware and cyber hacking is a serious threat to businesses and governments—even communities. Major cities like Atlanta have already been “held hostage” by ransomware. It’s rare for any market…whether it’s IT and social media platforms, agricultural commodities, or pharmaceutical markets…to escape disruptive innovations in their space. The pharma industry was able to accelerate the mRNA vaccine development and deployment to deliver vaccines in less than 1/4 the time such R&D and production had ever been done before. And there’s no one I’ve spoken to that really understands the implications of the rise of cryptocurrency—its future impact, both intended and unintended consequences, remains uncertain.

COMMUNITY RESILIENCE

Communities—their governments and citizens—can’t escape the acceleration of wicked challenges. The recent COVID crisis has shone a light on myriad issues plaguing communities that struggle for recovery and renewal, such as:

Urgent services adequacy

Infrastructure deterioration

Inequity and access

Polarization/division

ICUs and ERs are currently overrun with medical crises, with communities seeing increased waiting times. Patients must drive hundreds of miles for care. And there are still too many unnecessary deaths. Local infrastructure that was already deteriorating is under tremendous stress. Persistent inequity and the lack of access to basic services (to meet basic needs) was exacerbated. Meanwhile, rising polarization and division—fueled by extremism and facilitated by social media—now pits community members against each other. Protests become violent.

GLOBAL THREATS

And at the broadest level, global threats are arising and loom over our collective future as a species. Some of the more obvious adaptive challenges are:

Pandemics

Rising authoritarianism

International corruption

Climate crisis

The recent pandemic was predicted; epidemiologists are still confident (and unsettled) that other pandemics—perhaps more deadly—are just outside of our gaze into the future. Rising authoritarianism, fascism, and kleptocracies are spreading from nation to nation and threaten democracy around the world. The Pandora Papers provide only the most recent documentation of how money is hidden from taxation, when instead it could be applied to address the issues defined here. Oliver Bullough’s book, Moneyland, provides an nearly exhaustive systemic analysis of the broad influence of global corruption. And the most complexifying adaptive challenge of all is the climate crisis. We are already experiencing “once in a century” weather events—but on an almost weekly basis—that are disproportionately impacting the poorest and most disadvantaged populations.

Adaptive Challenges

The problems mentioned above (relatable examples to businesses, NGOs, governments, and our communities)–and many others like them–are what Ron Heifetz originally defined as adaptive challenges. What do I mean by that? Here’s a brief description from my colleague, Craig Weber:

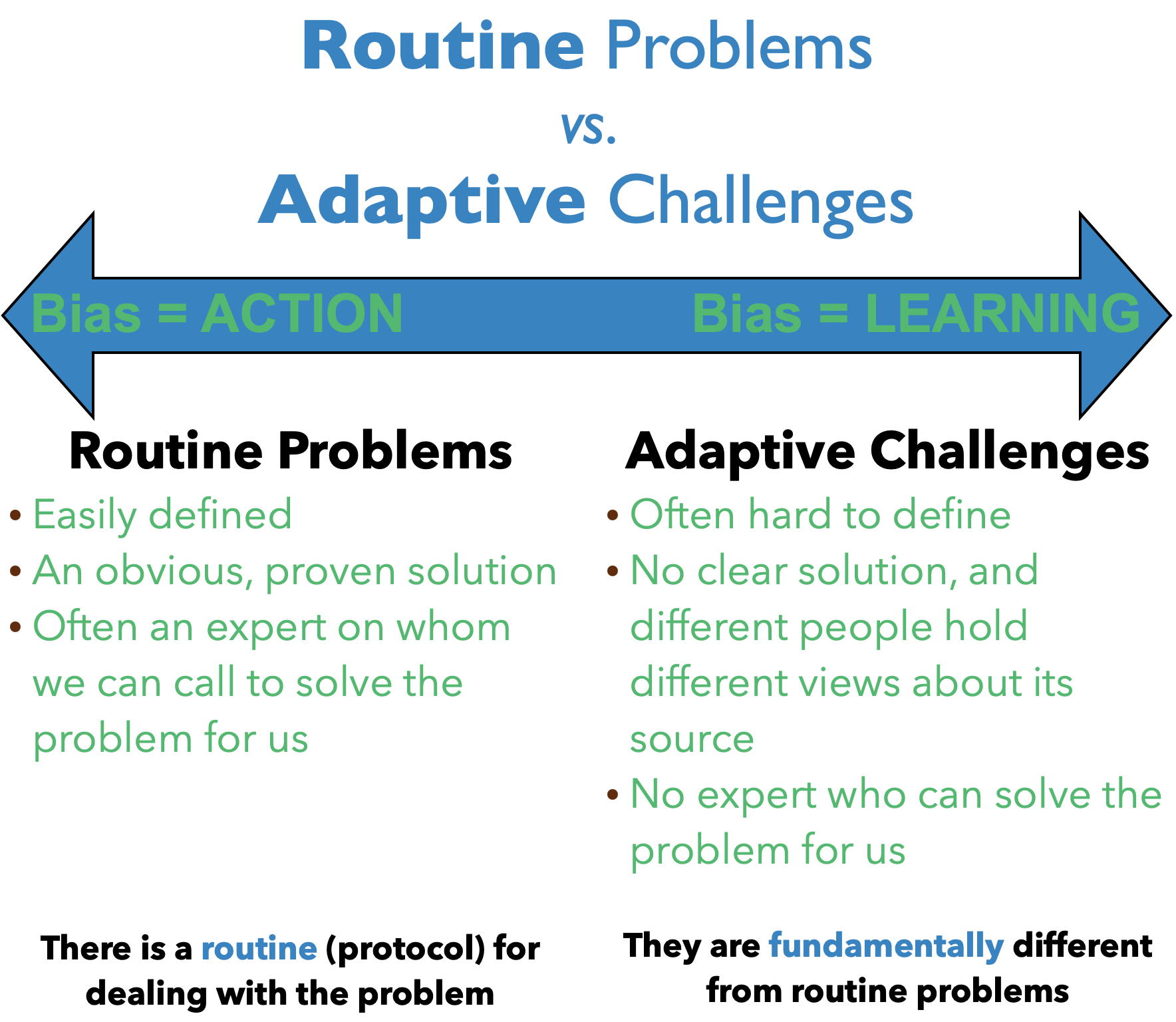

“All our difficulties fall somewhere on a spectrum; at one end of this spectrum we find routine problems, and, at the other end, adaptive challenges. A routine problem isn’t considered routine because it happens regularly, but because we have a routine for dealing with it—a protocol, a process, or expert on which we can depend for a reliable fix. A routine problem may be irksome and expensive, but at least we’re in familiar territory and know what to do about it.

When we’re facing an adaptive challenge, on the other hand, we’re off the familiar trail in uncharted territory where there are no proven routines, protocols, solutions, or experts. To successfully negotiate an adaptive challenge we must work and learn with others to navigate the alien terrain. All the problems we face in life fall somewhere between these two distinct poles…

…

. . it’s more important than ever to recognize the distinction between routine and adaptive issues because they each require a profoundly different problem solving approach. For a routine problem a bias for action is appropriate. We have a routine, we know what to do, so as Nike suggests, we should “just do it.” But for an adaptive challenge—where there is no clear routine, no proven process, and no ready expert who can save the day—a bias for learning is essential. Why? To navigate our way over unfamiliar ground we must roll up our cognitive sleeves and work with others to figure out the best way forward. We must orchestrate, in other words, a process of adaptive learning.”

—Craig Weber, Conversational Capacity

If we’re to effectively resolve adaptive challenges, our formal and informal institutions must orchestrate a process of learning—and success hinges on how well we can encourage a diverse set of interest groups to honestly share and learn from their contrasting and often competing perspectives. This work can get messy. It is messy precisely because they are adaptive challenges.

Most of us would love to have an “out of the box”, “easy to follow” checklist to solve any challenge. Just like doctors have a procedure for setting a broken arm, we’d love a checklist—that if followed—would address the challenges listed above.

We’re led to believe this is possible because our experience has proven many problems can be solved using a checklist approach. These are what Weber refers to as routine problems. They aren’t routine because they happen routinely. They are routine, because we have a routine for solving them. The problems are easily defined…the diagnosis is straight forward. There’s often an expert who has an answer, an approach to solving the problem. And there’s a protocol, a checklist, a set of standard operating procedures for resolving.

Adaptive challenges, by definition, have no check list and no expert who can fix them. They require guiding a process of learning by those who are experiencing and likely contributing to the problem. They first need to integrate their perspectives in ways that help them best understand what is happening. They need a common picture of the price being paid by the issue remaining unresolved. Then they can determine why the problem exists. All of this understanding must be generated first—and collectively—prior to identifying solutions. Otherwise, solutions might at best just miss the mark; at worst, they could create nasty unintended consequences.

Before trying to solve any issue it’s essential to determine the % of the issue that is adaptive. The further to the right on the continuum—the more the problem is solely an adaptive challenge—the more SysQ is required to solve the issue.

Most of the issues we desperately must address have some routine elements mixed with some adaptive ones. The field of public health provides easy to understand examples. Epidemiologists have established reducing the percentage of the population classified as obese will reduce the prevalence of many of the most serious health conditions (e.g. heart disease, cancer, and diabetes). There are many practices individuals can adopt that will help them reach a healthy weight, such as diet / nutrition, fitness, and adequate sleep. However, getting even one person to adopt these preventive behaviors is much harder then telling them to do it. And getting a large segment of the population to adopt them is an immense adaptive challenge. If current predictions (Harvard School of Public Health) are accurate, over half of the United States could be obese by 2030.

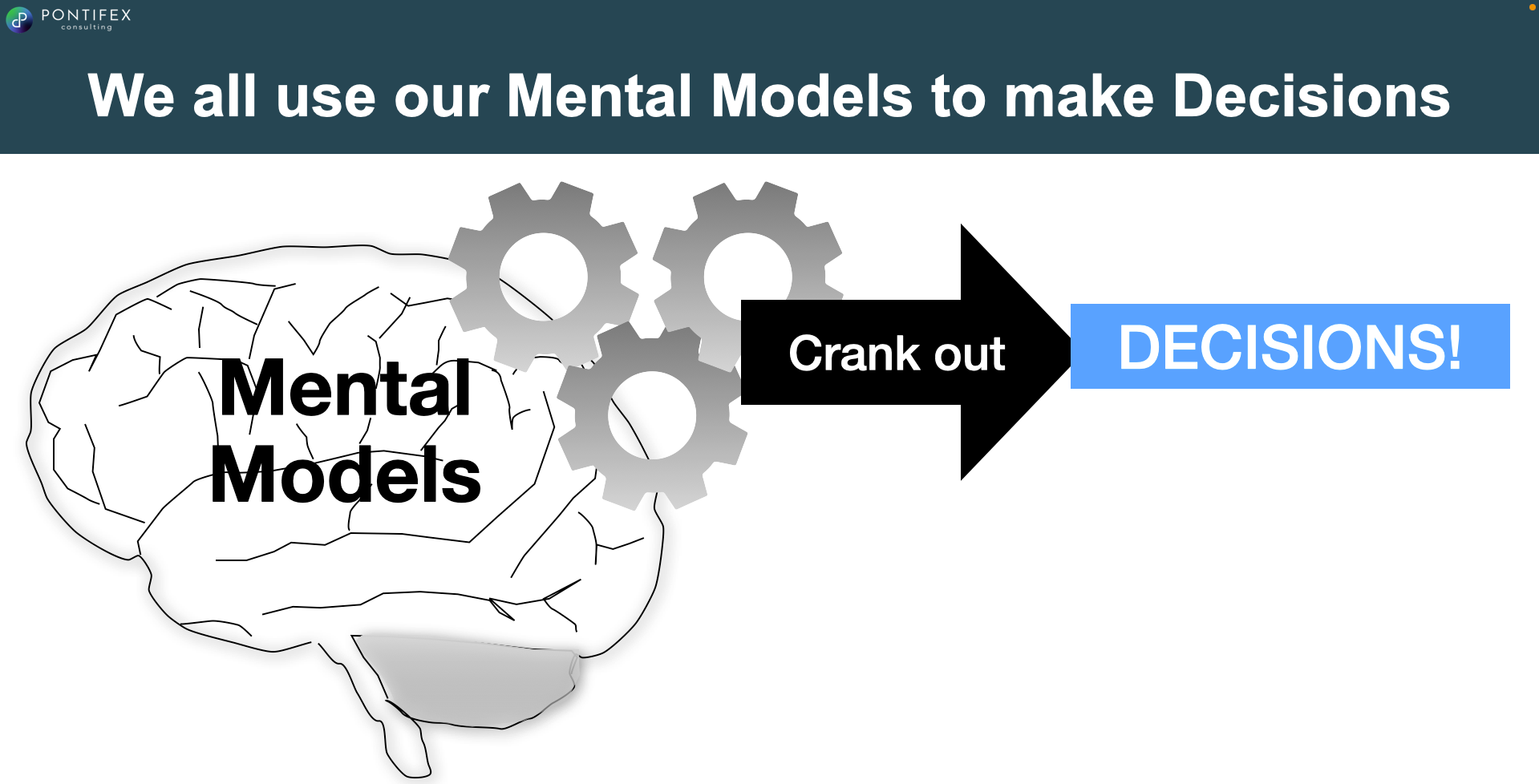

Learning When Facing Adaptive Challenges

Our mental models determine our current solutions, policies, protocols, and processes—our current know-how. Mental models are the set of assumptions we use to make sense out of the world. Our mental models are often unconscious, untested, unarticulated—and incomplete. We use our mental models constantly. For example, we may ask “Why do my children consistently misbehave right before dinner?” Assume I’m framing this as a problem because I would like to see a reduction in this behavior (i.e. my vision of the future). That’s the evaluative component of my mental model, that it’s good to reduce that behavior. Also, assume my hypothesis is that their blood sugar being low causes the behavior. That’s the causal component of my mental model. In that case, my strategy will be to feed them a well-balanced (mix of proteins and carbohydrates) snack right after school and observe if this seems to address the issue. That’s the “best lever” component of my mental model. I’ve just observed reality, framed what I thought was important, determined the cause, and identified a solution. That’s the process of using my mental model. I’ll need to observe to see if my hypothesis is correct, and adjust my mental model based on data. That’s the ongoing improvement aspect of using mental models.

We have mental models about our organizations—our current and potential markets, how they’re changing, how my team performs, etc… Our mental models are often implicit and unconscious, yet they are what we must use to assess what’s happening, make projections and forecasts as to what might happen in the future, and what must we do differently if we wish to change that future. We don’t have reality in our heads, so our only choice is to use our mental models, as flawed as they are. The fundamental goal of systemic intelligence (SysQ) is to surface and improve our mental models in a way that will help us better understand the world, and be more effective humans, organizations, and communities. Improving our capacity to do this may be the most important work of this time in history.

Our mental models about people, places and things arise from a deeper set of assumptions about the world, what are often referred to as paradigms. Do I focus on events? Or perhaps look for patterns? Do I think in terms of linear cause and effect? Or do I think about reciprocal causality (feedback loops driving behavior)? Do I believe unintended consequences often occur under well-intentioned strategies…or not? These are attributes of our paradigms, our way of seeing the world.

In order to address adaptive challenges we need to surface and change our mental models…and sometimes it even requires delving into our paradigms. To change mental models or to shift paradigms requires systemic thinking. But the only way to address workplace issues, understand and navigate complex markets, build more resilient communities, and address global threats is to apply SysQ.

Future blogs will provide concrete practices you can use to better solve the adaptive challenges you face. In this process, you will increase your SysQ. The first blog in this series gives an overview of the SysQ Process. Subscribe to SysQ Matters to learn more about how you can build your SysQ and apply it to your most pressing problems.

SysQ Principles Highlights

One of the most significant steps to solving problems is to accurately choose and define the actual problem. This may seem like either an obvious activity or unnecessary. Why do we need to spend time getting clear on the right problem? The problem should be easy to see. It’s that fire we need to put out, right? Well, not so fast. After reading the post above, it should be clear that not all problems are created equally. If we misdefine an adaptive challenge as a routine problem, we’re not going to solve it. When the Challenger disaster happened, NASA defined the problem as a routine one. They developed new protocols, rules and policies. The fundamental problem was an adaptive challenge: the culture. The inevitable result of improperly defining the problem as an adaptive challenge was the Columbia disaster: the same “can do” culture contributed to a series of errors that cost millions…and lives. The key SysQ step here is to choose the Right Wall. This means to Frame the Right Problem. And use the routine problem / adaptive challenge continuum to accurately assess how far along the continuum to the right—towards the 100% adaptive challenge end the issue is. If so, we need to Expand the Field of Vision (look at longer term trends, look across sectors and silos), Focus on the Physics (understand how time delays and feedback loops are contributing to the issue), and Seek Leverage. If we don’t have the Right Wall, no amount of smart thinking will solve the issue if we’re working on the wrong problem.