ADAPTIVE LEARNING

PIVOTAL SKILLS FOR COLLECTIVE IMPACT

Learning Smarter…Faster…and Together

Craig Weber and Chris Soderquist

Weber Consulting, Pontifex Consulting

Communities around the globe…

…face an expanding range of

tough,

interconnected,

complex problems:

poverty

racism

violence

police and community tensions

environment degradation

access to education

obesity

mental illness

climate change,

health inequity

…just to name a few.

These problems—and many others like them—are what we refer to as adaptive challenges. What do we mean by that?

An explanation follows (first written in Conversational Capacity by Craig Weber).

All our difficulties fall somewhere on a spectrum; at one end of this spectrum we find routine problems, and, at the other end, adaptive challenges. A routine problem isn’t considered routine because it happens regularly, but because we have a routine for dealing with it—a protocol, a process, or expert on which we can depend for a reliable fix. A routine problem may be irksome and expensive, but at least we’re in familiar territory and know what to do about it.

When we’re facing an adaptive challenge, on the other hand, we’re off the familiar trail in uncharted territory where there are no proven routines, protocols, solutions, or experts. To successfully negotiate an adaptive challenge we must work and learn with others to navigate the alien terrain.

All the problems we face in life fall somewhere between these two distinct poles.

. . it’s more important than ever to recognize the distinction between routine and adaptive issues because they each require a profoundly different problem solving approach. For a routine problem a bias for action is appropriate. We have a routine, we know what to do, so as Nike suggests, we should “just do it.” But for an adaptive challenge—where there is no clear routine, no proven process, and no ready expert who can save the day—a bias for learning is essential. Why? To navigate our way over unfamiliar ground we must roll up our cognitive sleeves and work with others to figure out the best way forward. We must orchestrate, in other words, a process of adaptive learning.

If they’re to effectively resolve adaptive challenges, communities must do just that–orchestrate a process of learning–and success hinges on how well they can encourage a diverse set of interest groups to honestly share and learn from their contrasting and sometimes competing perspectives. This work can get messy.

“Someone exercising leadership is orchestrating the process of getting factions with competing definitions of the problem to start learning from one another.”

—Ron Heifetz

Collective Impact ⇔ Process of Learning

Collective Impact is a process that has been developed to help guide communities and networks through such “messy,” adaptive learning processes.

In their article, Collective Impact, Kania and Kramer make this point: “Reforming public education, restoring wetland environments, and improving community health are all adaptive problems. In these cases, reaching an effective solution requires learning by the stakeholders involved in the problem, who must then change their own behavior in order to create a solution.”

If implemented effectively, Collective Impact has the potential to produce an agile process of learning. But in far too many cases it fails to live up to this potential because the process bogs down and loses momentum. Many of its once passionate leaders become disillusioned and drop out of the process. These are almost universally smart, passionate, committed people, so what’s going on here. Why does this happen?

It happens because simply understanding these challenges isn’t enough. Collective Impact requires powerful new mindsets and skills to be effective, once the laborious task of choosing a path forward has been accomplished.

Peter Senge, who brought the concept of systems thinking into leadership curriculum in his book The Fifth Discipline, co-authored an article with Kania and Kramer: The Water of Systems Change. The authors state, “Attempting to foster systems change without building the capacity to “see” systems leads to a lot of talk and very little results. One does not learn to play the violin in a three-day intensive course. Real learning—developing a capability to do something we could not do before—demands deep commitment, mentoring, and never-ending practice. The same is true for capacity building among collective actors such as performing arts ensembles or high-performing sports teams. This is no different when it comes to fostering systems change.”

No capacity building ➡︎ No ability to “see” anew ➡︎ No systems change.

Period.

“Attempting to foster systems change without building the capacity to “see” systems leads to a lot of talk and very little results.”

—Kania, Kramer and Senge

Here’s a way to think about the need for specific skills that support a strategy. Running a Collective Impact process can be compared to running a complex play in basketball. A team may have a strategy for how to execute a perfect triangle offense, for example, but their strategy is useless if the players don’t know how to pass, dribble, and shoot. Their strategy is nothing more than a pipedream if they lack the basic skills necessary for playing the game.

We think the same thing often happens in Collective Impact efforts. Communities have a process and a strategy, and they have smart, passionate people, but they’re lacking the requisite skills to put their smarts, passion, and strategy into useful play. Just as there are fundamental skills needed to run the triangle offense in basketball, there is a set of adaptive learning skills essential to leading an effective Collective Impact process.

So what are these skills?

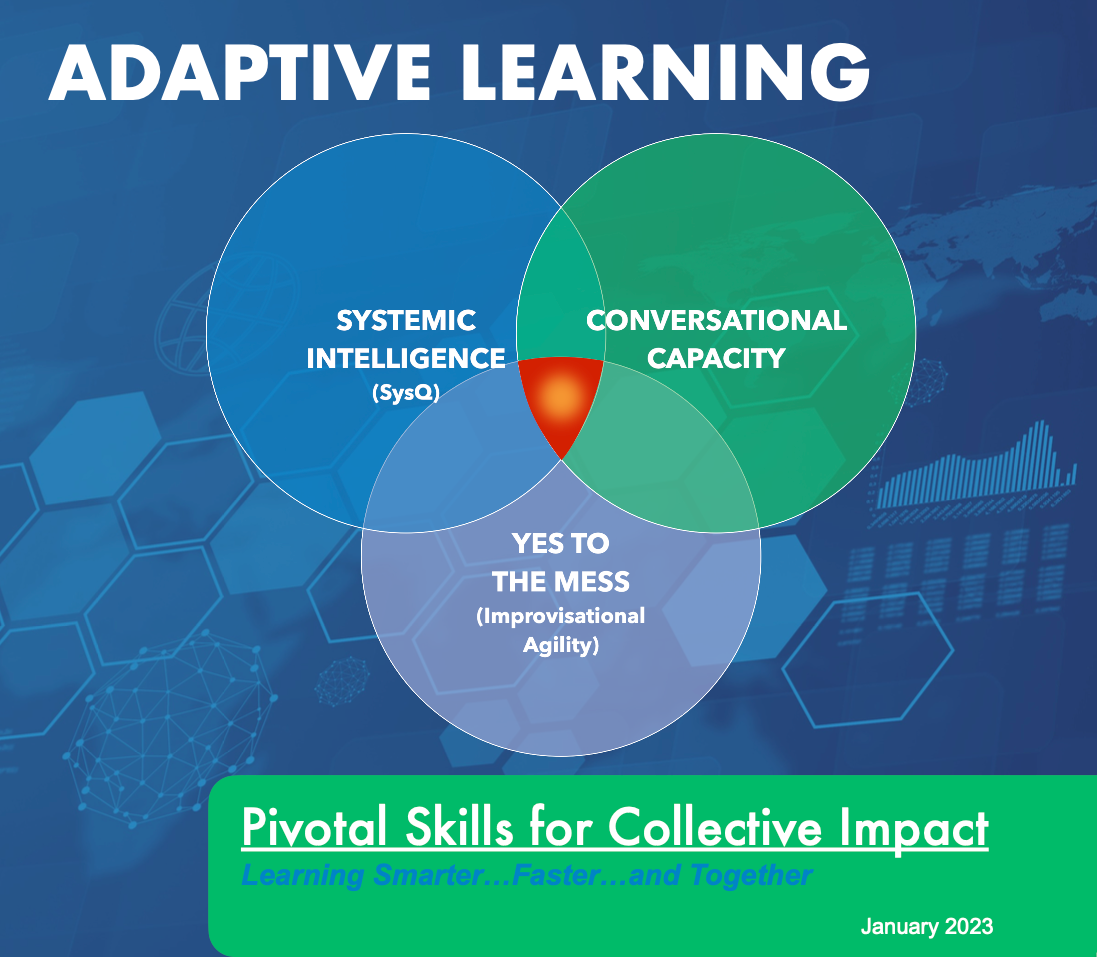

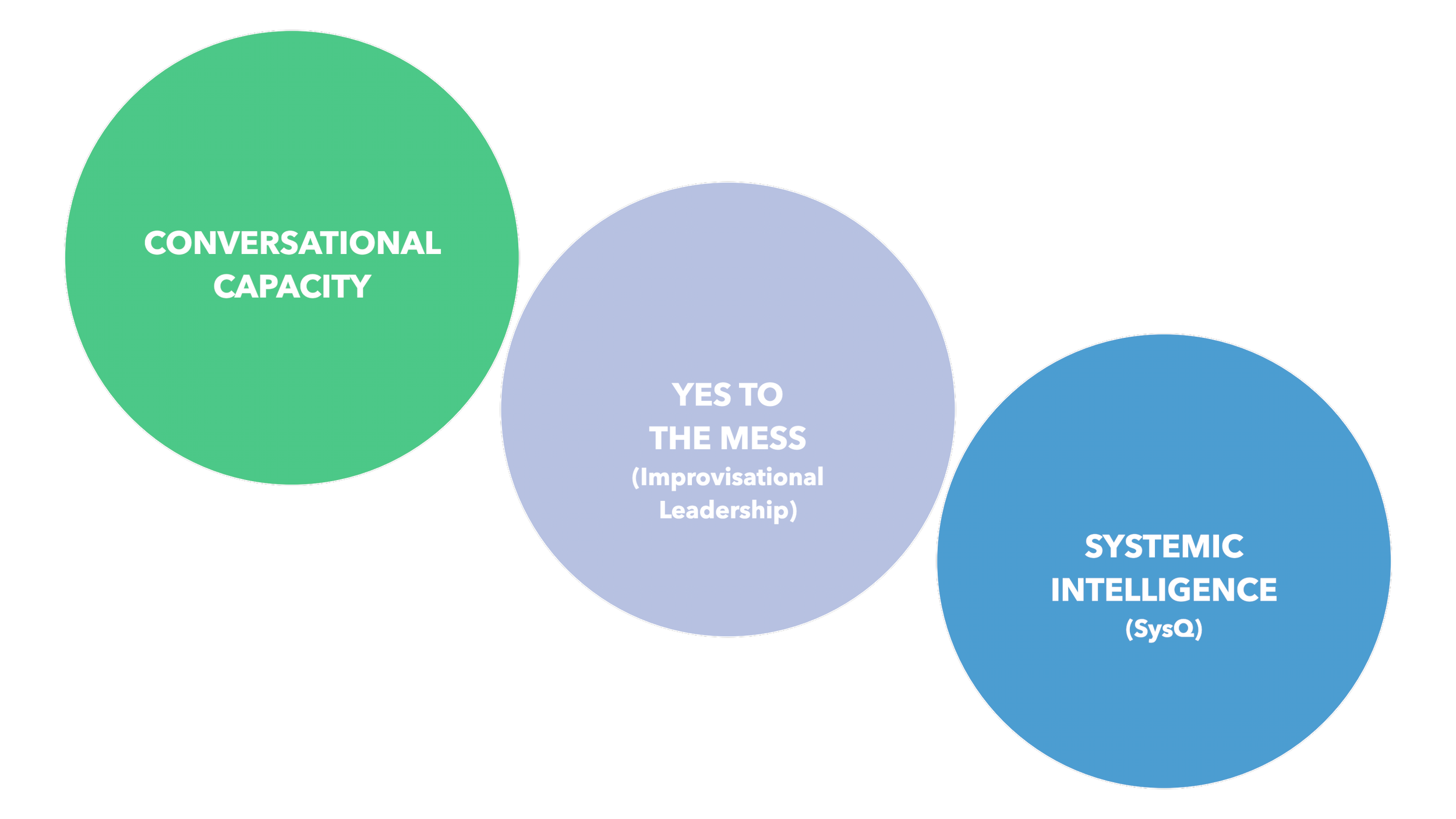

Three Skill Sets Essential for Adaptive Learning

Three Enabling Competencies of Adaptive Learning

We think there are three essential and interrelated competencies for adaptive leadership and learning:

SYSTEMIC INTELLIGENCE

CONVERSATIONAL CAPACITY

YES TO THE MESS (Improvisational Agility)

“Just as there are fundamental skills needed to run complex plays in basketball, there is a set of adaptive learning skills needed to run an effective Collective Impact process.”

These three enabling competencies help you find the leverage needed for fundamental improvement, by accelerating a process of learning in which community members engage in rigorous and balanced conversations about highly emotional topics.

Put differently, adaptive learning skills help people and communities learn faster, smarter, and together.

SYSTEMIC INTELLIGENCE (SysQ)

Systemic Intelligence (what we refer to as SysQ) is the capacity to identify high leverage places to intervene. With limited time and resources, it helps communities identify changes that provoke the most profound and sustainable improvements.

Low leverage occurs when you fight the “physics” of the system, when the more you push it to change, the more it pushes back. High leverage occurs when you work within—even leverage—the laws of physics.

Low leverage occurs when today’s problems come from yesterday’s solutions because you failed to predict unintended consequences. High leverage identifies the fulcrum of a problem and designs the intervention around it.

Low leverage strategies, even when apparently successful, often erode a community’s ability to solve future problems. High leverage solutions build capacity; they make the community stronger and more resilient.

This high leverage competency is referred to as Systemic Intelligence (SysQ). This is in line with the initial concept of systems thinking. We no longer call it systems thinking because everyone has their own—typically watered down, anemic, non-operational—definition of systems thinking.

SysQ isn’t working on systems. It’s more than that. Systemic Intelligence refers to how we think about systemic issues It’s the THINKING. It’s far more than the oft-adopted, overly simplistic, and unhelpful perspective that “it’s all complex and connected.”

At its core, SysQ is based on a foundational principle: Behavior is generated by structure. How we’ve “structured” our resources, organizations, and communities—which come from the structure of our thinking, our mental models—generates the behaviors we like…and those we don’t. If we’re to create the future we’ve envisioned, we’ll need to understand how we’ve structured things and how we’ll have to change that structure to produce the behaviors we want.

The mindset required for systemic intelligence is an unwavering commitment to understanding the whole set of relationships (structure) that drive important “real world” behaviors.

Those high in SysQ assume we’ve been using boundaries too narrow to understand the problem, focusing on our little part of the system—our silo (e.g. education, health, public safety, etc.)—as if it’s the most important. It also assumes we’ve not been thinking hard enough about how the world “really works”, by overlooking time delays, vicious cycles (and other feedback loop behavior), and especially unintended consequences.

The skills of SysQ provide a rigorous way to frame issues, broaden and deepen your understanding, map out assumptions about cause and effect, and focus on the issues that really matter—making sense of the system, in effect, so you can actually see it.

This is critical. If you can’t see the system you’re trying to improve, there is no way to identify the best ways to make constructive change. Systemic intelligence makes you stronger and smarter. It takes you from a place of being stuck as a reactive, “woe is me,” victim of circumstance, to a place where you have the wisdom and confidence to intervene in ways that make a profound difference.

“If you can’t see the system you’re trying to improve, there is no way to identify the best ways to make constructive change.”

Systems thinking isn’t working on systems. That’s just glorified process improvement.

Systems Thinking should be the ability to apply a systemic framework to solve complex, adaptive challenges.

This type of systems thinking—this capacity—is SYSTEMIC INTELLIGENCE.

Conversational Capacity

In our world of mounting complexity and change, building organizations, teams, and projects that work well under pressure is more important than ever. But while it’s easy to put together a team that works when facing simple problems, building a team that performs when things get tough remains an elusive and frustrating task. The reason, according to Craig Weber, is that traditional team building overlooks the most important piece of the puzzle.

That missing piece is conversational capacity—a team’s ability to have open, balanced, learning-focused dialogue about difficult subjects, in challenging circumstances, and across tough boundaries.

A group with high conversational capacity can perform well, remaining on track even when dealing with their most troublesome issues.

A group lacking that capacity, by contrast, can see their performance derail over a minor difference of opinion. In this sense, conversational capacity isn’t just another aspect of effective teamwork—it defines it. A team that cannot talk about its most pressing issues isn’t really a team at all—it’s just a group of people that can’t work together effectively when it counts.

This is a critical competence for a successful Collective Impact process that requires people to communicate and collaborate about tough issues and across challenging boundaries.

Sounds simple, right? All a team has to do is boost its conversational capacity and all will be well. Unfortunately, it’s not that easy. In the quest to build capacity we face a formidable obstacle: human nature. It turns out that reliably effective teams are hard to build because primal aspects of our nature, rooted in the powerful fight-flight response, actually work against teamwork.

“Conversational Capacity is the ability to have open, balanced, learning-focused dialogue about difficult subjects, in challenging circumstances, and across tough boundaries.”

—Craig Weber

Fortunately, there’s hope. There’s a proven discipline—a veritable conversational martial art—that allows people and their teams to remain open, balanced, and learning-focused as they tackle their most troublesome issues. Armed with this discipline, communities, organizations, and teams can respond to tough challenges with greater agility and skill, performing brilliantly in circumstances that incapacitate less disciplined teams.

“Yes To The Mess” Learning (aka Improvisational Agility)

The Yes to the Mess skill set is akin to agile learning—which is often associated with software development—can most easily be understood as the skill of improvisation.

Two key aspects of improvisational agility are particularly useful for Collective Impact work: an affirmative bias, and a “learn as you go” approach. Our friend and colleague Frank Barrett, author of the wonderful book Yes To The Mess, explains this better than anyone:

Managers frequently find themselves in the middle of messes not of their own making, in over their heads, having to take action even though there is no guarantee of a good outcome, and relying on imperfect information. Jazz players face the same issues, but what makes it possible to improvise, to adjust and fall upon a working strategy is an affirmative move, an implicit ‘yes’ that allows them to move forward even in the midst of uncertainty. Problem solving by itself will not generate novel solutions. What’s needed is an affirmative belief that a solution exists and that something positive will emerge.

The improvisational mindset assumes that no matter how messy, how difficult, or how confusing the current predicament, there is always a creative and constructive path forward. At its core, the improvisational process stems from an affirmative mindset.

But in addition to an affirmative bias, other essential skills of improvisation are rapid experimentation and embracing errors. This approach reflects the observation of Kurt Lewin who noted that the best way to learn about any system is to try and change it. Rather than sitting back and waiting to intervene until all the necessary information is available, you get to work with the best information available—and then learn as you go.

“Organizations thrive…by building a capacity to experiment, learn, and innovate—in short, by engaging in strategic, engaged improvisation. The model of jazz musicians improvising collectively offers a clear and powerful example of how people and teams can coordinate, be productive, and create amazing innovations without so many of the control levers that managers relied on in the industrial age.”

—Frank Barrett

An Über Competency

Without these three competencies a group will almost always underperform, especially when it’s facing an adaptive challenge. They combine to form an über competence—a meta-skill—that turbocharges the effectiveness of a person, team, organization, or community.

Systemic Intelligence (SysQ) can help a group identify the high leverage actions that will spark the most constructive change;

Conversational Capacity enables a group of smart people to work smarter by balancing candor and courage and curiosity and humility under pressure;

and the skills of Yes to the Mess help people work in more open, flexible, experimental ways…in situations where rapid learning is the key to progress.

Together these competencies empower people and groups to come together to tackle their most pressing issues in a more focused and cogent way.

We’ve compared these competencies to the skills needed to play music, a sport, or other similar endeavors. But they’re more than that. They’re the skills needed to excel at these activities.

What distinguished basketball players like Larry Bird and Magic Johnson from their peers wasn’t just their skills at dribbling, passing and shooting—it was their über ability to see the full court and imagine how things were playing out, their ability to selflessly pass the ball and to work with all players on the team, and their ability to turn a broken play into a basket.

“Elite basketball players are distinguished because of their ability to see the full court…to imagine how things are playing out…to selflessly pass the ball…and work with the whole team. And their ability to improvise a broken play into a basket.”

The same thing is true of jazz. “The model of jazz musicians improvising collectively offers a clear and powerful example of how people and teams can coordinate, be productive, and create amazing innovations without so many of the control levers that managers relied on in the industrial age,” says Barrett. “An improvisation model of organizing creates a kind of openness, an invitation to possibility, rather than leaning toward a narrowness of control.”

This is why the interrelated skills of

SYSTEMIC INTELLIGENCE,

CONVERSATIONAL CAPACITY, and

YES TO THE MESS

(Improvisational Agility)

are so important to Collective Impact endeavors.

“These competencies empower people and groups to come together to tackle their most pressing issues in a more focused and cogent way.”

Ensuring the process performs at its potential requires building and using the adaptive-learning skills we’ve just described. They’ll not only help you make the constructive changes you’re seeking, they’ll also help you build an even more connected, resilient, and learning-focused community.